Dressed for the coldest conditions, I step down from the boat’s loading dock and on to the zodiac. I feel a little awkward, because I’m still finding my way in this Antarctic armor.

I had walked down four flights of stairs from my room to the dock, but it was not enough to stretch out my long underwear. The bottoms are still stiff and resistant from their last wash, and the shirt feels tight. I’m wearing four layers on top, including three jackets (smock, puffy, and outer shell), all of their hoods over my head, obstructing my peripheral vision. Thick winter gloves cover my fingers. In my pocket is, of all things, a bag of my Dad’s ashes, which adds to the bulk. I can feel the bump it makes on the right side of my jacket as I sit down on the side of the inflatable boat.

The zodiac sprints away from the mothership. I have to turn my whole body toward the front of the boat—the amount of layers makes it hard to twist my upper half—to see the icy waters ahead. Two big icebergs, the undersides bursting with an absolutely gorgeous glacial blue color, fill my vision. They tower above my head as we cruise past. Jagged peaks hug the coastline in all directions, including behind us, where offshore islands form a protected pocket for this calm waterway.

Seeing it all, I smile. I made it to Antarctica. The White Continent. The most unique land mass in the world—physically and historically. Antarctica is the coldest, highest, driest, and windiest continent on Planet Earth. It was discovered and reached by man for the first time not much more than 200 years ago. Many of history’s most colorful explorers—James Cook, Ernest Shackleton, Roald Amundsen, and Robert Scott, to name a few—were involved in the search for, discovery of, and mapping of its icy waters and ice-covered landscape, with many lives lost in pursuit. Whalers once processed whales by the thousands upon its volcanic sands. It’s also home to one of the most badass birds in the world.

We come around the corner and I see my first penguin. It’s swimming twenty or thirty yards from the zodiac, looking the same as a dolphin swims, super powerful underwater, extremely graceful as it comes up to breathe, popping up just like a dolphin, but instead of the top fin, you see its arms as the distinctive feature, tucked back by its side. Soon a few more penguins become visible, bopping about between the bergs. The guide identifies them as Gentoo Penguins, marked by their red “lipstick.” I reach for my camera and feel the ashes again.

I want to honor my Dad here, on this trip, for several reasons. Next June will be ten years since he died, and despite the fact that he was a homebody, traveling—or, at least, my pursuit of it—was something we really bonded over. Antarctica has been on my radar for 15 years, going back to my first year of travel journalism. It was a place I always wanted to be sent, for various reasons, and to be here now, so close to my Dad’s “anniversary,” fills me with a lot of emotion. It would have been special to share it with him. Maybe a ceremonial offering, like the spreading of his ashes, could suffice.

I know what you’re thinking. It’s been ten years. Why the hell do I still have his ashes? It wasn’t intentional. I was on a war path cleaning out closets and drawers one cold, rainy fall day this October when I discovered them. At first, I was a bit horrified, kneeling there in front of the open closet. It’s not unusual for people to save ashes, but to find them in a plastic bag in the bowels of a bedroom closet ten years later, completely overlooked and forgotten—I’m a terrible son.

But, ultimately, I allowed myself (conveniently) to see the discovery of the ashes, however initially bleak, as a gift. I could bring the last piece of my Dad to Antarctica with me—and leave him there. This was something I had done elsewhere as a way of remembering him, of replenishing my gratitude. My Dad’s gravestone is in New Jersey, but his ashes rest around the world, as far away as Easter Island, one of the most remote places on our planet.

I admit that these ceremonies were mostly for me. I liked the way they made me feel, to remember that we are still on the journey together. So, what’s one more? Antarctica, as fate would have it, could be the mother of them all, the perfect place to acknowledge the passing of a decade.

A decade. Wow. It still feels like yesterday. I remember the weekend he died, and I remember that it began brilliantly. I was in Sarajevo, Bosnia, and my buddy Bert and I had befriended a spontaneous and enterprising young bartender who agreed to drive us the three hours to Durmitor National Park in neighboring Montenegro. I don’t remember the exact price we negotiated. But it was reasonable enough and the exchange rate friendly enough that we, with the understanding that it may be difficult to find a ride back, and with the understanding that he might have something to offer us as a friend, proposed to double it and also to pay for his hotel room if he would hang out and drive us back in a few days, whenever worked for him, maybe after the weekend. He asked if his friend could come, and we said of course, even better.

I remember being really excited walking back to the hotel. It was a decent enough interpretation of one of my personal travel mantras—don’t hire a guide, find one. Obviously, we were hiring him, so it wasn’t a perfect execution. But, this was no run-of-the-mill, booked-online tour. Two friends were driving us to another country, spur of the moment. There was no itinerary, other than to get there. Perfect? No. Acceptable? Damn right. Even better was knowing that the successful creation of this spontaneous adventure meant that we had carried ourselves well, and thus, that we had traveled well.

The road between Savajevo and Durmitor was a beautiful, winding mountain road, and we were seeing this foreign land for the first time with the windows down, in the company of two new unexpected friends, listening to some Turkish rock band they had put on when we inquired about their taste in music. When we arrived at the park Bert and I rented bikes in the tiny town of Zabljak on the edge of Durmitor and loaded a backpack with bread, meat, and ajvar, the local red pepper paste that we’d come to love, and a bottle of the Bosnian Lozovaca rakia Bert had bought in Sarajevo.

We pedaled uphill for a while. It was a gorgeous day, the mountains green, the ground soft, and we laid down in an open meadow under the sun. A city boy at heart, Bert commented how he wanted to make more time in his life for nature. I remember telling him how I wanted to buy a massage table, and maybe go to school on the side. It was a very relaxing afternoon, just the refresh I needed after a week of cramped train travel through Eastern Europe.

The next morning was when I received word. I remember the three hours back to Sarajevo, crying in the backseat, throughout all the rises and falls of the mountain road, with Bert holding my hand at times. It must have been such a bizarre, unexpected plot twist for our two new friends in the front seat (and probably for Bert as well), the sudden departure, the American they barely knew, strong and confident the day before, now broken down in the backseat. But they understood. Heartbreak is not bound by borders or language. (Ironically, despite the horrible ending to the journey, Bert wrote a great travel writing piece afterwards, a tribute to the fun we had wandering through cities on that trip).

That warm Montenegro mountain sun, which I remember clearly, is certainly nowhere to be found here in Antarctica. Air temperatures are topping out around 32, but when the wind blows, it can drop in a hurry, bringing that cold, icy air right into my face. Luckily, I wasn’t expecting the Caribbean, and as Alfred Wainwright famously said after his coast-to-coast walk across Britain, “There’s no such thing as bad weather, only unsuitable clothing.”

I remove my ski googles—which I would really recommend bringing if you ever go—so I can look out over the landscape without alteration. The guide kills the engine and our zodiac gently bumps against the coastal rocks, and we unload onto the shore. My boot swings out of the boat and onto the rocks, and I take a few steps inland, onto the snow. A smile comes to my face. The plan is to snowshoe a loop, going up the ridge a bit and stopping somewhere along the way for a bird’s eye view of the lagoon.

We prepare to put on our snowshoes, but before we do, the guide calls our attention and gives a little speech. It turns out to be a buzz kill. We are not to sit down, nor are we to put anything on the ground, including backpacks. Nothing is allowed to touch the ground other than your feet. If we have anything in our possession that could blow away—like food wrappers—we are to hand them over immediately. We are not to go to the bathroom.

I get it—I’m glad to see tour operators protecting the land—but I’m also annoyed. My brain does its selfish thing. So, even though whalers left behind entire ghost towns, even though many countries have scientific research stations on the continent, even though the Brits built a post office on an idyllic island amongst the ice, I cannot sit down in the snow? Obviously, I had hired a guide, not found one. What about the ashes, then? If I can’t sit in the snow, and I can’t pee on the snow, and I can’t put my pack on the snow, I am guessing ashes are out of the question?

Whatever. I decide that I’ll do it in secret, shake it out the bottom of my pants or something, like Andy Dufresne in Shawshank Redemption. I could probably bend over and bury it when the guides are distracted with another traveler. It will all work out. He will be set to rest.

We set off in a line. I’m trying to shake the slight disappointment I feel about not being able to further engage this place, to feel at home, to sit down and take it in. After a few minutes of walking, I begin to feel more comfortable and athletic in my gear, and I begin to relax. It’s impossible to be in a bad mood, to lose gratitude. The sun is peaking out of the clouds, illuminating the ice in the lagoon, and, for the first time, I see the blue of the Antarctic sky beyond the snow-covered peaks. I can see icebergs, humpback whales are spouting, there are penguins on the rocks near the water, and the fresh air feels fantastic. It’s beautiful, and I feel so happy.

A few hundred yards later, I hear a woman fall behind me—she had never snowshoed before and kept tripping over herself—and I stop and turn back to help the guide get her up. It’s easier with two people on the sloped hillside. The good deed has an immediate kickback. By stopping to help, the people in front of me get farther ahead. Now, when I begin to walk again, I have space in front of me. I have room to breathe. I feel the ashes in my pocket with every step, and I just smile about it.

Helping someone always makes me think of my Dad, because he spent the better part of his life helping others as a police officer and homicide detective. He went through some pretty crazy experiences. One day he responded to a bank robbery, had his windshield blown out by a shotgun (yes, like the movies), but instead of running, like I suspect I might, he continued to engage. He and his partner ended up catching all three criminals. He shot one of them. It changed his life. Ruined it in some respects. His mental health, for sure. His innocence, without question.

I catch back up to the group along the ridge. Everyone is stopped on this perch, looking out over the lagoon. The view is incredible, the perfect spot for an ash scattering (I had always selected scenic overlooks in other locations). I step away from the group and turn my back to them, keeping the lagoon in front of me. I reach in my pocket and feel the bag of ashes.

But something stops me. I begin to realize that breaking the rules would feel wrong in this regard. An illegal burial for a law enforcement official? Seems backwards, karmically at least. A cooler side of me begins to prevail. After all, I’m down here for work, and I want to come back, so I need to behave myself. Plus, now that I really see how special Antarctica is, I suppose, no matter how over the top, I can respect the rules for now, in this situation.

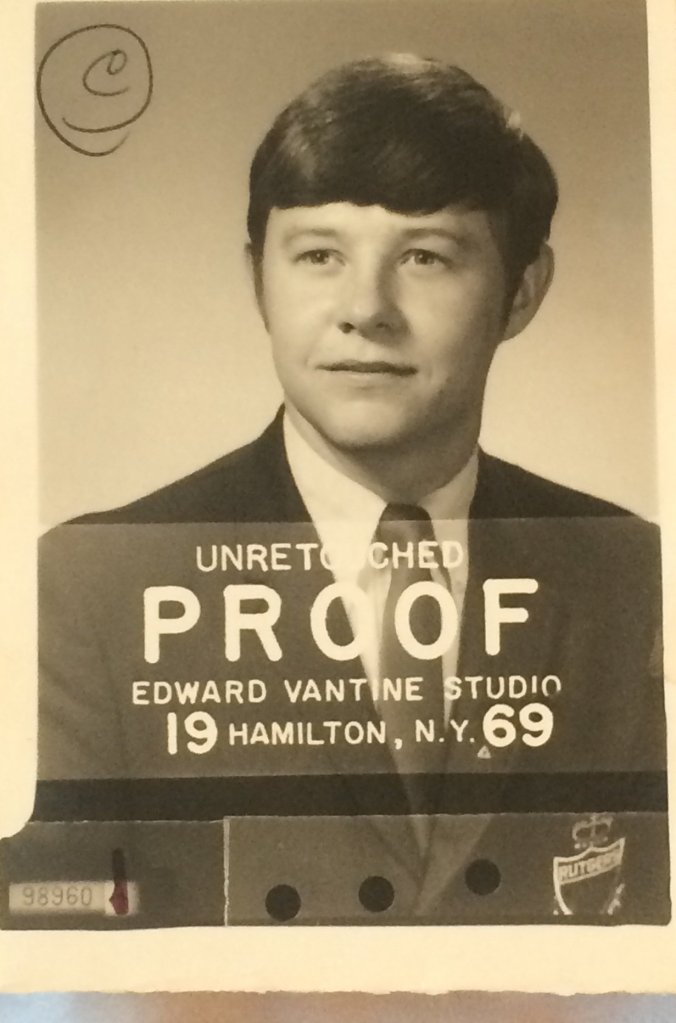

Instead of the ashes, I pull out only the prayer card that’s beside the bag. I take a deep breath as I scan the landscape, the snowy hill leading down to the berg-filled lagoon. I see my Dad’s smiling face on the front of the card—one of the few good pictures I have of him—then turn it over to see the poem on the back. I read the words silently to myself:

Do not stand at my grave and weep.

I am not there. I do not sleep.

I am a thousand winds that blow.

I am the diamond glints on snow.

I am the sunlight on ripened grain.

I am the gentle autumn rain.

When you awaken in the morning’s hush

I am the swift uplifting rush

Of quiet birds in circled flight.

I am the soft stars that shine at night.

Do not stand at my grave and cry;

I am not there. I did not die.

My Dad didn’t see much of the world. Funny enough, he probably wouldn’t want to go to Antarctica. But he loved the idea for me, and he helped me get to a place where I was happy. He was then truly happy to see me happy. What more can you ask of a parent? Things were not always perfect, far from it at times. The most important thing for my Dad and I was that we did not give up—we kept trying, and it paid off.

I put the prayer card back into my pocket. I’m grateful for the bond we created together, and the effort we put forth to do so. Because of that, we can still be together today. I remember looking out the window on the way back to Sarajevo and feeling like everything was different. The feelings of freedom I felt the day before, when he was alive, were gone. I had become comfortable about the future, but all of a sudden, I felt unsure of what was to come. I wondered if I had what it takes to continue the journey without him—not physically, but spiritually.

Turns out, ten years later, I’ve never really had to answer that question, because after the initial grief, after telling myself over and over again that he was gone, I came to find that he, to my surprise and delight, never left. One relationship ended, but another began.

Yes, I had wanted to give him a proper ceremony here on my big trip to Antarctica. I wanted to honor him in that way. But my Dad never wanted a fuss made about him anyway. Besides, I already have what I want. I’m here on the White Continent. I’m thinking of him. I’m still following the path he helped pave.

It’s a good thing to feel, and it’s something I’ll need to hang on to tightly as I travel back home for the holidays. I’ll need to remember this feeling when I’m home for Christmas next week, confronted once again by his absence, by the passing of ten years as if it were ten days.

Walking back down the ridge, the sound of the shoe on the snow becomes melodic, medicinal. The lagoon is directly in front of me. The cold air feels fresh in my lungs. My brain starts buzzing.

Maybe it makes sense to spread the ashes closer to home, where he spent his life. Maybe that’s the best idea. I’m not sure. But I know that, either way, standing in the cemetery, I’ll think back upon this glorious place in front of my eyes—the diamond glints on snow, the breath of whales, the play of penguins—for strength.

Looking at his name on the gravestone, I’ll think back to these moments in Antarctica and remind myself that there’s no reason to worry, no reason to cry.

He is not there. He did not die.

Good to hear from you, Will. You made it to Antarctica?! Awesome! 🐧Fitting tribute for your dad.

Hi Will,

There is something so unique and flowing about your writing. I always want to get to the punchline/the moral/the wrap-up, but then once there, you leave me wanting more. What a beautiful and fitting journey for you and for your father. How wonderful that you made it to Antarctica; a place I fear I will never see after having a trip booked there that cancelled during Covid-19. I’m glad you made the journey and will take my own joy in that, as your purpose was much worthier than mine. Just getting that I made it to the 7th Continent sweatshirt will have to wait. You make me feel as though I have already been. All good things for you in 2025. Travel frequently and safely…..hoping our paths cross again sometime!

Great read Will, thanks for sharing those memories of your dad. What a momentous trip, of both mind and body. Absolutely cool!